Mac Whitney was born in Manhattan, Kansas, on August 3, 1936. He attended the College of Emporia in his native state for one year. He completed his undergraduate studies at Kansas State Teachers College in Emporia, earning the B.A. degree in 1958. Over the next several years, Mac Whitney invented and built various equipment and machinery items, farmed, worked in a boiler factory, and did graduate work at Kansas University (1961) and at Kansas State Teachers College (1966). From 1967 to 1968, he earned his Master of Fine Arts at Kansas University.

During the 1968-1969 academic year, Whitney was an art instructor at Eastern Illinois University in Charleston. He moved to Texas in 1969 and maintained a studio near Ovilla, Texas. In 1979, Mac Whitney was awarded a commission by the City of Houston to build a large-scale sculpture funded by grants by the National Endowment for the Arts and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Whitney was awarded an individual artist grant by the NEA in 1979.

Essay by Susie Kalil

Lucin, 2010, welded stainless steel, 13' x 5' x 4'. Carrizozo, 2010, welded steel, 20' x 5' x 8'

Mac Whitney's steel sculptures have an intense effect on all who engage them. Working without assistants or fabricators, his hands-on approach to the metal makes poetry out of industry. Few sculptors have given raw steel new life as magically as Whitney. Every fold, hollow, plane and bulge is given lively form, producing a sense of dynamism, as if the inert material were pulsating with metaphysical energy. Surfaces are pierced, pitted, channeled or intertwined so the whole looks like multiples in a writhing embrace or twirling dance. Every alignment, every lyrical hairpin curve speaks of aesthetic decision. For the most part, the works have an inspired tension and emotional resonance not anticipated in one's first contact with them. Industrial components are almost invisibly but flexibly joined together. Currents ebb and flow from one surface to another, thus unleashing the hidden life held with the form.

Experience taught Whitney an essential point; that sculpture is an engineering problem, one that deals with manipulating or defying the constraints of gravity. Throughout, he refused to valorize the art object over "blue collar" labor. Although Whitney lived in Texas since 1969, he grew up on a Kansas farm and later worked on huge oil field pressure tanks in a boiler factory. In the use of steel as form and primary material, Whitney's process-oriented sculptures bring to mind not-so-distant times when tinkering, basic craftsmanship and resourcefulness were necessities of daily life. For all its elegant facility, Whitney's art has a Midwest quirkiness that runs continuously back to childhood experiences. Indeed, his most poetic sculptures always express a sort of existential gawkiness—that strange and loveable effect of what, in these confusing times, it is like to be a person. Whereas the sculptures embody a tough mix of aesthetic refinement and intuitive chutzpah, they also work hard for pleasure. Distilled, self-assured, historically conscious without being mannered, the pieces seemingly swing between an out-of-control obsessiveness and the exacting restraint of understatement.

The contradictions within Whitney's sculptures, of course, are in sharp contrast to the skill with which they are realized. Industrial and organic, mechanical and sexual, inside and outside, passive and aggressive, functionalism and poetic license are just a few oppositions which the sculptures manage to blend in surprising ways. The power from which the distinctive works derive their strength evolves from the artist's personal mechanics and intuitive vocabulary he has gradually built up over the years. Inasmuch as they recapitulate memory, audacious formal rigor, and hard manual labor, the sculptures also give the viewer the artist's sense of angle, surface, texture, space and surprise at the perception of solid and void. Whitney is far from a finish fetishist, yet the viewer can't resist touching, even caressing the configurations of rounded volumes, smooth planes and tough "skin."

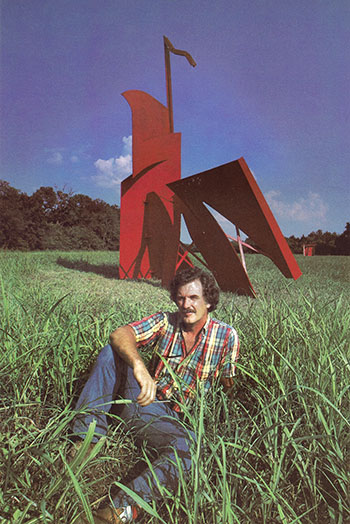

Mac Whitney with Laredo, 1978

Each vibrates. As in the best jazz compositions, they are works of the inspired instant, approximating the freely drawn swiftness of calligraphy. Industrial process has its own cycle of birth and dissolution. But look into Whitney's work, at any point, and observe it growing, extending. It is solid and moving in time; it evolves and devolves, always becoming more complex. As vehicles for articulating negative space, Whitney's sculptures evoke those by David Smith which allow emptiness to seep in—not so much displacing space as defining and activating it. Whitney also shares a similar penchant for primitive totemic sources and "drawing" in space. In any case, Whitney's shapes swell and lift in taut axial successions, both lyrical and erotic. The rugged, massive qualities of the material and scale are played off against the ease and grace of their movements. Most certainly, the forces from which these distinctive sculptures derive their power evolve from the conscious desire to engage the viewer. Admittedly, the sculptures suggest the bends and folds of the body and the pull of gravity. More often than not, they rise from the ground as monumental presences, confronting the viewer as tantalizingly elusive beings. Significantly, the works bring to bear a profound identification and magnetic force between the sculpture and the viewer's body. To walk around them is to sense a reflex you may not have felt so clearly before—pull, sensuousness, illusion; but also insecurity, risk, danger. Component parts take on a strange internal energy—things come out of things, pushing, nudging, linking their outer parts.

Evident is a renewed focus on material decision-making and through it, on the poetics of seeming to display the mind in operation. They are familiar forms, but now with a cumulative pathos illustrating an undefined anxiety. The reverberation of muscular forms and undulating "lines" induces an intensely vertiginous effect. Whitney's sculptures unfold in time. A shape seems recognizable only for an instant before transforming into another related form. They beckon us to crouch down, duck underneath and carefully inspect their exposed masses and voids. The eye is led over and through sensual curves and slides; we are projected into an almost balletic whirl. Move around Whitney's sculptures and watch how the characteristics change with the light of day. The slightest shift and they yield a dazzling array of new and complex information—facets now consumed, now multiplied in the play of reflected light, a constant state of tension between abstract concept and natural form, between finished form and metamorphosis. One can't help but be struck by a connection: the time Whitney gives the work and the time spent on it by the viewer. For one's response to the sculptures certainly has something to do with the care and fine-tuning that have gone into them. And therein rests Whitney's special gift—to temper the aloofness of his forms with the omnipresent quality of his human touch.